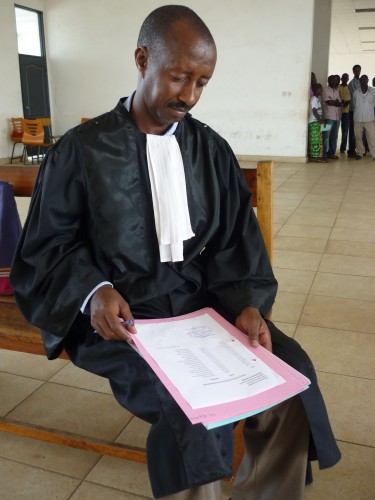

At ten o’clock, IBJ Legal Fellow Janvier Ncamatwi arrives at the courthouse in Bujumbura, Burundi. Though he is there on schedule, he still has to wait for his clients to arrive, because the prisons lack the vehicles to reliably transport accused detainees to court.

Janvier is expecting to handle ten cases this morning. There is a boy accused of stealing while working as a domestic servant; the lawyer suspects that there may be a dispute regarding the terms of employment which underlie the accusation. There are also two women among his clients, one accused of allying with bandits or rebels, while the other was arrested and imprisoned accused with having had an abortion, which is forbidden in Burundi. Another juvenile client is facing an accusation of rape.

The vehicle arrives with the detainees and the court session can begin.

The boy accused of rape is 17 years old. An uncle of the alleged victim had lodged the complaint against the boy. Janvier suspects the case stems from a personal conflict rather than any criminal act. The boy is from Tanzania and had been working in Burundi as a mechanic, but now he has lost two years of his young life behind bars, awaiting justice. The two years he has spent in pre-trial detention is equal to half the total maximum prison sentence he may face as a juvenile.

The accused only speaks Swahili, a language not commonly heard in Burundi; this may be one of the reasons he has been made to wait for so long. The prosecutor’s file says that the boy had confessed, but Janvier challenges the reliability of the claim based on the language barrier. Though Burundian law provides that accused persons should have the benefit of communicating about the case against them in a language they can understand, this is an unfulfilled promise. There is no translator provided.

Going into the hearing, there are several other problems that Janvier has identified in the case files. The prosecutor claims that a doctor’s report corroborates the charges, but this document is nowhere to be found in evidence. There is no witness supporting the accusation, and the long time that has passed since the arrest will make the case difficult to prove. Generally, a prosecutor is obliged to present an accused person before the court within a 15-day time limit. The limit is subject to extension, but the two years this boy has been kept in pre-trial detention is completely unreasonable.

Today is finally the boy’s day in court, which he can now fortunately face with a lawyer by his side. When he is called to testify before the judges, a Burundian man speaking Swahili steps up to help him communicate. In the course of the hearing, Janvier and his client learn the news that will finally bring the boy’s ordeal to its long-awaited end: the accuser has written a letter recanting the accusation.

Of the ten clients Janvier was expecting to help today, four of the detainees were not brought to court. The exact reason for their absence is unclear; prisoners may have been released by the juridical commission, but it is also possible that they were simply left behind. Of the six clients who were present, only half of the case files were brought to court by the proesecutor. The cases without files could not be heard, so those clients were forced to return to their prison cells with no progress made in their cases.

This was just one day in the life of one IBJ lawyer working in Burundi, but it perfectly illustrates why the need for help is so urgent. Without access to a lawyer to look out for him, the accused boy might never have been exonerated. Burundi struggles to meet even the most basic requirements of a functioning criminal justice system: missing files, lacking evidence, and unconsciable delays. By bridging the gap between the laws and their just implementation, IBJ is striving to deliver on the promises made in human rights guarantees.